Not long ago, I led a small group of iPhone photographers on a photo walk through downtown Austin, focused on capturing urban decay. For this particular assignment, our goal was to explore the beauty and texture in scenes of aging and disrepair—a kind of photographic entropy. We were seeking to find life in the overlooked, in what many might consider the remnants of time: the rust, the cracked walls, the chipped paint. There’s a richness in these signs of wear that tell a story of their own, and in photography, there’s an art to capturing that narrative.

Among the group was an older participant, perhaps in her late 70s. As we began exploring, I noticed she held back from engaging with the scenes of decay that captivated the others. She was reluctant, visibly uneasy, sidestepping any chance to frame these scenes in her lens. And, being the quiet observer that I am, I found a moment to ask her what she felt about our focus on urban decay.

Her reaction was immediate—her posture tightened, and her eyes darted away. She told me, very plainly, that she wasn’t comfortable with themes of decay, or with anything that reminded her of death and dying. For her, these images hit far too close to home. It was a moment that stuck with me, a reminder of how sensitive mortality is as a subject for many.

Many of us, even those with strong faith are fearful and frighted by physical and emotional, decay, decline, and deterioration

Maybe, deep down, it’s our reluctance and inability to come to terms with the end of life.

I understand. I respect her feelings. Not everyone is ready or willing to engage with the notion of mortality and fragility, even in such an indirect way as through scenes of crumbling concrete or rusted metal. The fact is, it’s difficult to contemplate endings. To consider death and decay is to confront the transitory nature of our own lives—and that can be daunting, even painful.

But as photographers, we are storytellers, interpreters of life as we see it. The themes of death and decay aren’t just elements of photography; they are parts of the human experience. They remind us of the passage of time, of how beauty exists not only in growth but also in decline. To photograph decay isn’t to dwell morbidly on endings but rather to find a different kind of beauty in the natural cycle of things—a reminder that nothing, no matter how well-built, is permanent.

Ashes to ashes, dust to dust.

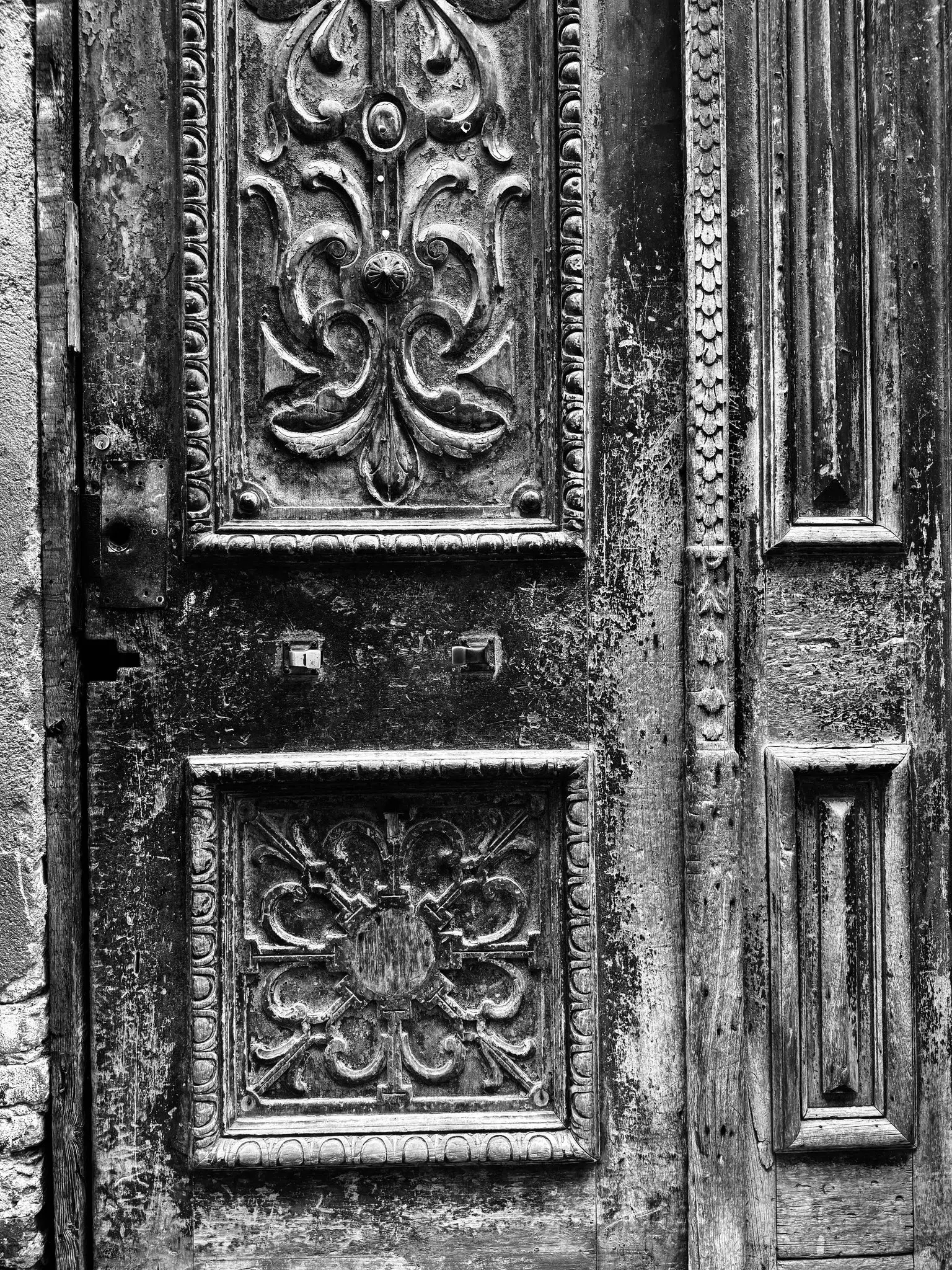

I encourage photographers of all kinds, regardless of their belief orientation, to embrace these themes. Just as we capture blossoming flowers or rising sunrises, we can find meaning in the stillness of a wilted leaf, in the shadows of an abandoned building, in the peeling paint on an old door. In photographing decay, we don’t only capture the end of a life cycle; we honor the full journey, finding value even in what others might deem past its prime. To face decay and death in photography is, in a way, to come to terms with these ideas emotionally. And through this, we allow our art to become a space where we can process, accept and ultimately embrace the reality of life’s transience.

So, the next time you have the chance, take a moment to notice what is often unseen. Photograph the cracks, the rust, the signs of wear. Allow these images to remind you that even in the face of inevitable endings, there is beauty—and sometimes, peace—in acknowledging what is real, what is transient, and what ultimately makes us human.

We live. We die. In between these cosmic but transitory bookends….we photograph.

Click.

Jack.