As a career photographer and more recently a humanist, I’ve often found myself navigating the intersections of art, wonder, and belief. Recently, over a quiet drink at a local bar, I had an encounter that stirred a reflection I’ve been mulling over for years: how can someone who doesn’t believe in a divine presence still marvel at the grandeur of the universe? For me, the answer lies not in faith but in perspective.

I had just pulled out my Field Notes notebook, settling into the moment with my pen and thoughts, and a Corona with lime, when a man plopped down on the bar stool beside me and broke my solitude with a loud, “What are you writing?”

“A blog post on Humanism as it relates to photography,” I replied casually, barely making even the slightest eye contact, expecting him to nod and move on. Instead, his face twisted in confusion.

“Humanism? What the fuck is that?”

I explained that Humanism is essentially a gentler way of saying atheism — the belief that one can live a life of meaning, wonder, and morality without attributing it to a god or higher power.

“Atheism?” he shot back. “Are you fucking kidding me? As a photographer, all you have to do is look around and see God everywhere.”

It wasn’t the first time I’d heard this sentiment, but after a week of atheism debates online, I decided not to engage further. I was mentally exhausted.

I just smiled back.

But his words lingered. As he noisily drained his beer and left without a goodbye, I realized how vastly different our attributions were despite our shared awe for the world.

Here’s the thing: I do look around and see beauty, majesty, and meaning everywhere. But I don’t see God. I see science, evolution, and the extraordinary unfolding of billions of years of cosmic and biological processes.

The wonder that this man attributed to divine creation, I attribute to the intricate mechanisms of nature and the universe — the way light bends through the atmosphere, the way gravity sculpts landscapes, the way evolution shapes life in all its diversity.

I call it…. “Amazing Space.”

While my bar companion might see Amazing Grace in a starry sky or a dramatic sunrise, I see the physics of light scattering and the stunning expanse of galaxies billions of years old. His sense of wonder is rooted in biblical faith; mine is rooted in faith of a different kind. But at its core, we’re both moved by the same thing: the sublime.

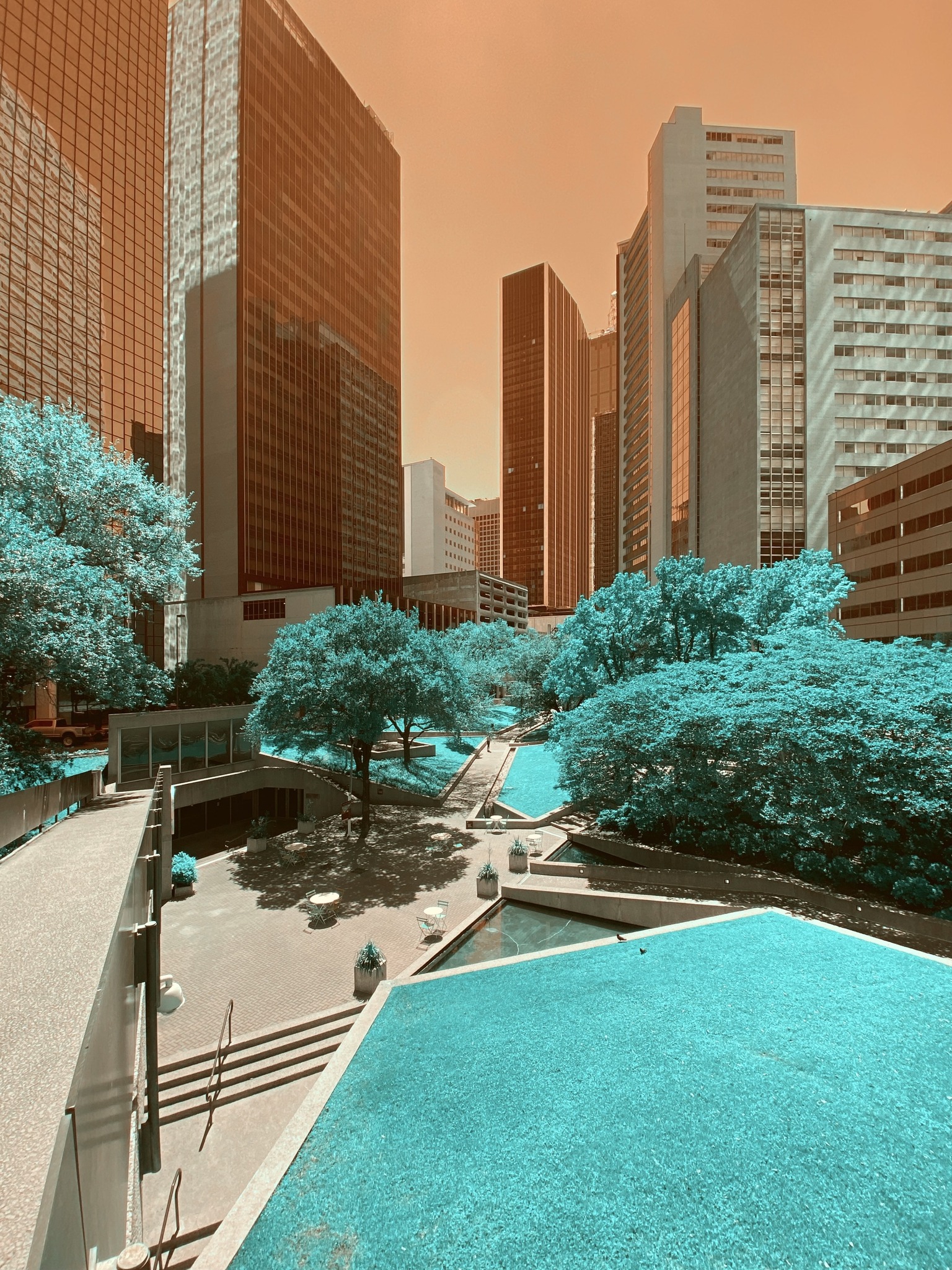

As a humanist photographer, my job isn’t to preach or debate. It’s to capture these moments of awe — to freeze time, light, and space into frames that help others see the world through my lens. Whether it’s the quiet dignity of a weathered face, the textured layers of a canyon wall, or the dense shadow from my morning latte, my goal is to share the beauty that I see without needing to attach it to a divine narrative.

Click.

My worldview doesn’t diminish the grandeur of the universe; it amplifies it. The fact that we exist at all — a product of chance and time, of stardust and survival — fills me with more awe than any creation story ever could.

The Biblical creation story? Really? Talk about absurdity?

In just seven days, an all-powerful being spoke everything into existence, sculpted a man from dirt, and handcrafted a woman from his rib. He set them in a perfect garden—except for that one forbidden tree. Enter a talking serpent (because, sure), who convinces the woman to snack on the wrong fruit, triggering eternal childbirth pain for all women (fair, right?). Meanwhile, the man, in a single afternoon, casually names every animal on Earth. And thus, humanity begins—thanks to a chatty reptile, a bad snack, and some divine “because I said so”.

But I digress.

The universe is a complex scientific marvel. Truly and remarkably.

To stand on a planet teeming with life, to witness light that traveled billions of years just to reach my camera sensor, to see the chaotic harmony of nature — this is my cathedral. This is my Amazing Space.

For me, photography is an act of reverence, not to a deity but to existence itself. It’s my way of saying, “This matters. This is beautiful. Look closer.” And in that way, perhaps, the humanist and the believer aren’t so different. We’re both trying to make sense of the wonder. We’re just writing different captions for the same photograph.

Click.

Jack.